Demystifying Equity in Ed Tech Hiring: A Practical Guide

This article presents a focused overview of equity (a term that can accurately be used interchangeably with “stock”) in Ed Tech designed to:

- Help professionals understand key facts about equity compensation in order to evaluate offers and develop their business knowledge base.

- Help hiring companies understand which vital facts about equity need to be communicated to employees. Being transparent and proactively educating employees helps prevent any unwelcome surprises.

Professionals without much exposure to finance often like to think that owning stock makes them “owners” of a certain portion of a company. Reality is a bit more complicated. And while every Ed Tech leader doesn’t need a sophisticated understanding of securities law, it’s important for any professional dealing with equity-based compensation to understand some foundational ideas. This knowledge is instrumental in rationally valuing equity offers, avoiding unrealistic expectations, and understanding the potential risks associated with owning stock in a startup.

Taking the time to understand startup equity going into a hiring process can also help a professional differentiate themselves from other candidates, demonstrating an aptitude for management-level thinking. We interviewed Ed Tech investor Steve Kupfer for this article, who notes that “many candidates don’t have the foundation needed to ask basic questions about equity and asking informed questions can really help establish a candidate's credibility.”

Equity 101

Equity offered as compensation is called “common stock” (more on what that means below). “Shares” are the basic measuring unit of this financial entity. While every share represents some kind of claim to company assets, the value of this claim depends on the broader financial context of the company. That’s why we need to understand a slightly broader picture to get some idea of what a quantity of common stock shares are worth.

Common stock offered to employees typically comes in one of two forms. First, is a stock option, which grants the option-holder the right to purchase a specified quantity of stock at a preset price (called the “strike price”) at some future date. The strike price is based on the company’s current valuation, the idea being that acquiring stock at this price in the future will be incredibly advantageous if the company’s value continues to grow. Second, the stock can be granted outright, although almost certainly with some form of restriction. For instance, a new hire’s stock issuance may only vest over a 5 year period dependent on continued employment.[1]

At a bare minimum, an individual considering equity compensation needs to know the total number of shares that a company has issued, which is referred to as shares outstanding. We can effectively think of shares outstanding as the denominator of stock ownership: if you own 50,000 shares of stock and the company has issued ten million shares, we divide to calculate that your stock represents .5% of overall shares. Clearly, we can do almost nothing to understand the meaning of a quantity of shares without this crucial denominator.

Understanding shares outstanding provides a basic idea of what portion of overall equity a quantity of shares represents. To really value this portion, however, we need to challenge a key misconception. It’s tempting to translate a “% of overall shares” number into a “% of ownership,” and get carried away with optimistic arithmetic. “I own .5% of the company. If they sell for $100 million, I’ll get $500,000!” These sorts of calculations are bound to end in disappointment, even if the underlying company is incredibly successful. To understand why, we need to dive a bit deeper into the basics of startup finance.

A simple fact helps conceptualize equity more accurately: shareholders do not own a company. Instead, shareholders hold a legally-defined bundle of rights that come with stock ownership. A shareholder--even a majority shareholder--can’t just walk in and take supplies from a company they own stock in. Nor can a stockholder draw on the bank account of this company. Rather, regular shares of stock come with a right to certain dividend payments (though dividends are virtually nonexistent in the startup context), a right to vote on certain key corporate issues, and, crucially, the right to sell the stock to someone else.

Here’s the key: a firm’s common stockholders aren't the only parties with some kind of legal claim on the value generated by that company. And not every share of stock comes with the same set of claims.

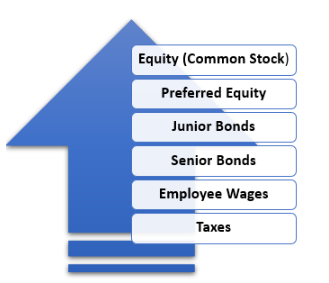

In finance, the complex network of competing legal claims to a company’s assets is known as the “capital stack.” These determinations can become incredibly complicated. Corporate lawyers can and do spend lifetimes mastering the nuances of this process. Fortunately, a high-level view of how startups raise money is sufficient for developing a better understanding of equity compensation.

Stacking Capital: Apportioning Risks and Rewards

Different investors receive different levels of legal claims to company assets. Ideally, these claims reflect the risk taken by investors who committed their funds at different stages in a company’s growth.

For instance, the founder and key early investors are the principal stakeholders likely to own “preferred equity.” If the company takes out any major loans to support its growth, these debts will be held by outside parties in the form of bonds (bonds also come with various tiers of seniority that needn’t concern us here).

When early investors commit their capital, they enter into legal agreements that precisely define how their money is going to be repaid over time. Senior stockholders, for instance, may demand that interest on their investment accrue in the form of even more equity. Or they may demand some form of “liquidation preference” (more on that below). These agreements will also define how much equity will be set aside to compensate key hires.

As a central part of the process for translating dollar investments into equity allocations, investors have to decide on a valuation for the company. This process is necessarily complex and uncertain, as the company’s current value depends on its future potential, which can be a very subjective determination.

HOW IS EQUITY COMPENSATION ALLOCATED?

The portion of equity set aside for use as compensation is referred to as the “option pool,” and typically ranges from 5-15% of the company’s valuation. Equity from this pool is offered at set amounts tied to different “bands,” or tiers, of company leadership. Companies make this calculation at their own discretion, and the total number of bands used can range from as few as three to as many as ten. Equity compensation tied to these bands can be counted as either a percentage of outstanding shares or a specific dollar value.

Steve Kupfer recommends that hiring firms use dollar amounts, noting that “percentages can change with any dilutive event. Dollars make it more tangible for employees.” These dollar amounts can, for instance, be calculated as percentages of each position’s salary. The following rules-of-thumb are based on the influential calculations popularized by VC Fred Wilson:

- Management Team (Chiefs, VP’s): .75 x Salary

- Director Level (Managers): .35x Salary

- Functional Employees (Engineering, Product, Sales, Marketing): .15 x Salary

- Others (Executive Assistants, Clerical Staff): .05 x Salary

The above amounts are far from set in stone, and hiring companies may not divulge the details of how they calculated a specific equity offer. But it’s important to understand that these amounts are usually pre-set for each position, not negotiated ad hoc on a hire-by-hire basis.

Either way, this common stock isn’t afforded the same level of protection received by other investors. The graphic below shows an idealized capital stack. Crucially, these different tiers of rights come into play not only in case of a sale, but in case of bankruptcy. If a business fails and is forced to liquidate, bondholders will be paid back first (after any operational expenses like taxes and wages are paid off). And common stockholders will be paid back last.

Common equity, then, bears the brunt of the risk. And early investors may even stipulate that their investment is paid back by several orders of magnitude before common stockholders receive value from their investment, payback amounts that can range from reasonable assessments of risk to outright predation.

Because of the number of lenders and preferred stockholders with senior claims on a company's assets, a startup often needs to post truly outstanding growth to generate serious returns for common stockholders. For this reason, it’s almost always better to approach equity compensation as a prospective bonus, while building your lifestyle and financial plans around cash compensation.

It’s also important for candidates to take steps to understand the broader financial situation of any company offering equity compensation. It’s impossible to know the future for any company, much less a startup, but getting a picture of the basic contours of their financial obligations is an essential first step for seriously evaluating a stake in their company.

The details of these finances can become quite complex; we suggest distilling this analysis into four fundamental points.

- Shares Outstanding: What’s the denominator? What percentage of total allocated equity do my shares represent?

- Valuation: What was the most recent valuation of the company? If initial investors made an unreasonable valuation of the company, it’s less likely to ever grow enough to repay them and begin rewarding common stockholders. Determining a precise valuation can be tricky, but candidates should ask themselves if the underlying business model makes sense. And if the investors are serious enough about understanding the Ed Tech market to generate a rational projection.

- Liquidation Preference: who will be paid in what order in the event that the company sells, liquidates, or declares bankruptcy? Preferred equity holders typically have a “liquidation preference” designed to protect their investment. This preference can simply equal their initial investment. Or it can be two or three times that amount. If too large, this amount risks substantially diluting the cash allocated to common stockholders.

- Financial Health: Is the company turning a profit? How long until it expects to go cash flow positive? How long can it sustain current operations without raising more capital? Getting a sense for the company's debt load is also key, as bondholders take priority over equity in the capital stack.

The ultimate value of equity will never be certain, even for shares in some of the biggest companies on earth. Building up some fundamental information clustered around these four points, however, provides a rational basis for deciding if an equity offer is a serious sweetener or an ephemeral promise.

For their part, hiring companies should never assume that candidates with non-financial backgrounds will have a functional understanding of startup equity. By not only being transparent about their own finances, but proactively seeking to “tell the whole story,” startups can facilitate a truly “equitable” compensation discussion.

[1]These two structures have slightly different financial implications. If a stock’s price never exceeds the strike price of a given stock option, that option has zero effective value. And, while the price may be advantageous, purchasing the stock will require a chunk of liquidity. If the stock is granted outright, it will be subject to income taxes whenever it vests.